Loads For The Long Shot

by Wayne van Zwoll

Center hits are easier when you’re close. But what if your only chance comes at distance?

AFTER A HUNTING EXPEDITION in 1873, George Armstrong Custer enthused: “With your rifle I killed far more game than any other … at longer range.” Remington’s Rolling Block had great reach. Ironically, on the Little Big Horn in 1876, Custer’s troops carried converted Springfields.

The accuracy of Rolling Block rifles suited them to long-range competition. In 1874 Remington engineer L.L. Hepburn began work on a match rifle like those used by the Irish in their recent victory at Wimbledon. The Irish had subsequently challenged the Americans to a six-man team event. Each shooter would fire 15 shots at each of three distances: 800, 900 and 1,000 yards. A newly formed National Rifle Association and the cities of New York and Brooklyn put up $5,000 apiece to build a range for the match on Long Island’s Creed’s Farm, provided by the State of New York.

In March, 1874, Remington unveiled a new .44-90 target rifle. In September a favored Irish team firing muzzleloaders bowed to the Americans and their Remington and Sharps breechloaders. Score: 934 to 931, with an Irish crossfire.

Meanwhile on the prairies, buffalo hunters cashed in with Rolling Blocks. During the 1870s and early ’80s, buffalo hides brought up to $50; skilled hunters could earn $10,000 a year. Brazos Bob McRae once killed 54 buffalo with as many shots from a single stand, using a scoped .44-90-400 Remington.

The 1874 Sharps was also popular. In a 1930 edition of the Kansas City Star, George Reighard explained how he shot bison: “I furnished the team and wagon and did the killing. (My partners) furnished the supplies and did the skinning, stretching and cooking. They got half the hides and I got the other half. I had two big .50 Sharps rifles with telescopic sights …”

“The time I made my biggest kill I lay on a slight ridge, behind a tuft of weeds 100 yards from a bunch of a thousand buffaloes. [After I’d shot about 25] my gun barrel became hot …. A bullet from an overheated gun does not go straight, it wobbles, so I put that gun aside and took the other. By the time that became hot the other had cooled, but then the powder smoke in front of me was so thick I could not see through it …. I had to crawl backward, dragging my two guns, and work around to another position …. In one and one-half hours I had fired ninety-one shots [and] killed seventy-nine buffaloes ….“

The Sharps Rifle Company folded in 1880, having no repeater to counter Winchester’s 1873 and 1876 lever-actions. A military budget constrained by peace contributed to the firm’s demise. Ironically, so did the lethal efficiency of market hunters. By the early 1880s, so many bison had fallen to the single-shot breechloader that human scavengers would glean more than three million tons of bones from the prairie.

You probably won’t have to dodge a cloud of black powder smoke to get your next shot at big game. Or carry two rifles to keep a cool barrel at hand. But some 19th-century habits are worth adopting. Getting as close as possible, for instance. Reighard didn’t launch bullets at bison from 1,000 yards, though his rifle could deal death at distance. To kill efficiently, he crawled within 100.

The current appeal of long shooting dates to the development of rifling in the 1500s. A spinning ball extended reach. It didn’t stray from sight-line as quickly as did balls from a smooth bore. But even accurate bullets hew to the laws of physics. Distance multiplies error. If your aim is 2 inches off the mark at 100 yards, it’s 6 inches off at 300, a foot at 600, two feet at 1,200.

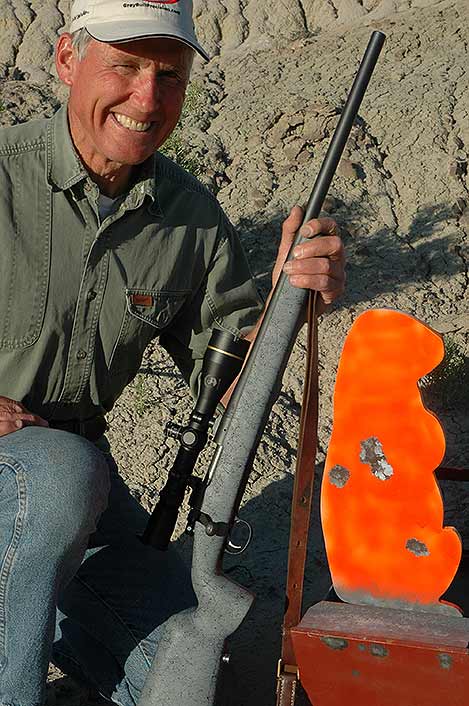

Anyone chasing “long-range” hits with new rifles, optics and loads will soon find that hardware has less bearing on accuracy than does marksmanship. Alas, the human body is a miserable shooting platform. It comprises twitching nerves, quivering muscles, pounding pulse, joints that slip under pressure. When we get excited we induce more wobble, then make a bad shot worse by yanking the trigger.

The high-power scopes that tap the reach of fast, flat-flying bullets show shooters how much a rifle actually moves as they aim. More hunters are using bipods to trim the tremors. I cut my teeth in competitive shooting and favor a sling. Hunting, I’ve used Brownell’s Latigo slings for 40 years. Tripod and sling become more effective when you improvise additional support for both your body and the rifle. Stump, rock, bush or backpack – all can help.

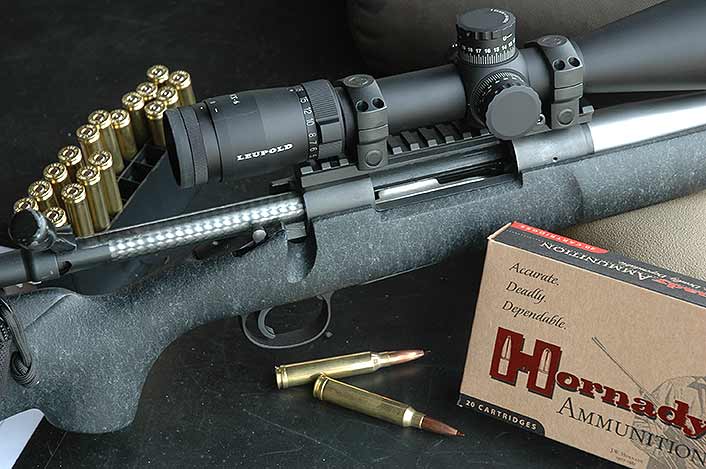

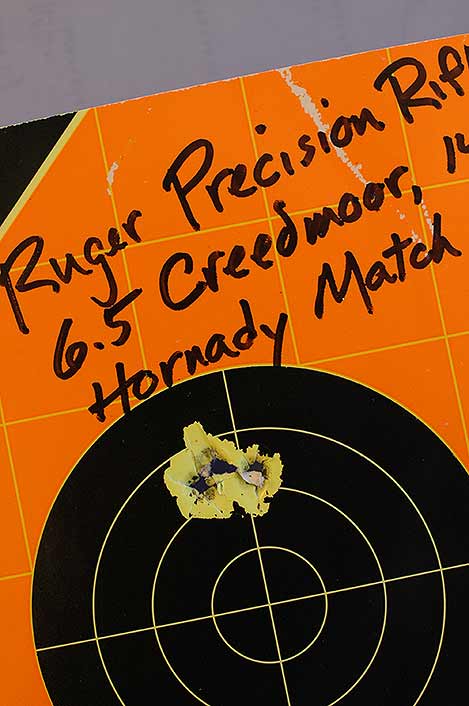

The fastest bullets aren’t necessarily best for shooting far. Nor are the most powerful cartridges. The .308 and .30-06 have punched the X-ring in the 600-yard stage of the National Match course for decades. The recent 6.5 Creedmoor gives hunters and competitive shooters a delightful combination of mild recoil and fine accuracy with a surprisingly flat arc at distance. Remember those first Creedmoor matches? Riflemen fired to four-figure yardage with thick lead bullets at black-powder velocities!

The race to faster, flatter-shooting loads began in earnest after WW II. Bullet design has evolved apace. Most modern hunting bullets have a sharp nose and a long, tapered ogives (the curve from nose to shank). About the only blunt bullets still popular are for heavy African game shot close, where sectional density matters a great deal. Bullet weight has less effect on trajectory and energy retention than does the nose profile. Consider two Nosler Partition bullets from a .300 Remington Ultra Mag (250-yard zero).

| Velocity, ft/sec | Energy, ft-lb | Drop, inches | |

| Muz. 200 400 | Muz. 200 400 | 300 400 | |

| 180-grain | 3250 2834 2454 | 4221 3201 2407 | -3.0 -12.7 |

| 200-grain | 3025 2636 2279 | 4063 3086 2308 | -3.4 -14.6 |

Similar rates of velocity loss show these bullets have nearly identical ballistic coefficients (.474 and .481). There’s negligible difference in bullet drop to 300 yards. The 2-inch disparity at 400 is just half as great as bullet dispersion from a minute-of-angle rifle!

VLD (very low drag) bullets seduce hunters who expect to shoot beyond 400 yards. Most of these sleek boat-tails have hollow noses with tiny cavities. These aren’t necessarily the most accurate bullets at 200-yard Benchrest matches. Since the first of these, in Johnstown, New York in 1947, competitors have favored light-recoiling rifles and bullets of high ballistic coefficient but relatively modest weight. As their rifles and loads have improved, so has their marksmanship. Not long ago in the UK, a sharp-eyed shooter drilled a .135-inch five-shot group at 100 yards, a 6.908 group at 1,000! At last check, the world’s record 1,000-yard group measures inside 2 inches, well under a quarter minute of angle!

At extended range, hunters benefit from long, heavy bullets that minimize wind drift and retain lethal punch. But such missiles must also expand across a spectrum of impact speeds, and hold together if powered into tough game up close. Engineers now tackle such challenges with help from devices like Doppler radar. A Doppler unit determines the position of a speeding bullet by reading a signal’s bounce. High-frequency microwaves gauge what’s called the Doppler shift in frequency, reflected from the bullet, to determine its velocity, time of flight and distance traveled.

Hornady’s Dave Emary, with Joe Thielen, Jayden Quinlan and Ryan Damman, applied Doppler radar to chart paths of fast bullets. They noticed irregularities in deceleration curves. The best, if unlikely explanation: a change in bullet shape during flight. “We found the polymer tips were melting,” says Dave. “Friction-induced temperatures can reach 800 degrees F. As BC (ballistic coefficient) is largely a function of bullet shape, tip deformation trims BC. Trajectories get steep; accuracy suffers.”

Jayden Quinlan emphasizes that “some bullets don’t go fast enough to reach the melt temperature of the polymer. Others – say, .22 varmint bullets – zip out the muzzle but decelerate quickly, given their modest BCs. Still others don’t spend enough time in the air to suffer tip deformation.”

Joe Thielen sums it up: “To oversimplify, impaired flight due to tip melt happens to bullets with a starting BC of .550, at 3,000 ft/sec exit speed, over ranges exceeding 300 yards.”

What about sleek hollowpoints used in long-range competition? Dave explains that “forming the jackets of hollowpoints at the nose introduces some variation. Also, OTM (open-tip match) bullets track erratically in gelatin. Tips can collapse inward, resulting in no expansion; or they shear, causing the shank to tumble. Polymer makes every meplat – the nose-end profile – the same. A poly tip can be engineered to initiate and control upset in game.”

Polymer-tip bullets aren’t just hollowpoints with a cap. Says Joe: “The core is designed to work with the tip, the cavity proportioned to cause the rate and degree of expansion desired.”

To reduce the variability of the drag component at distance, and its net effect on arc and accuracy, Hornady’s team came up with a hard polymer nose it calls the Heat Shield Tip. The patented material has a glass transition temp of 475 degrees F, eight times as high as that of nylon and Delrin. Its melting point of 700 degrees F is twice as high. That mark doesn’t quite match the heat endured by some bullets, but it ensures tip melt won’t be significant. Even bullets that generate more heat don’t sustain it for long.

The Doppler project yielded Hornady’s ELD-X bullet – for Extremely Low Drag, Expanding. Its tapered jacket has an Interlock “pinch” high on the shank, for more retained weight. Thick at the heel, the jacket brooks impact speeds to 2,900 ft/sec. Jacket taper up front, and the generous tip cavity, trigger upset down to 1,600 ft/sec. Dave Emary assures me the bullet wasn’t developed to encourage long shots at game. “ELD-X is simply more versatile than other bullets. It delivers superior accuracy and flatter flight, with lethal expansion and penetration over a wide range of impact speeds.”

Hornady applies a Precision Hunter label to ammo with ELD-X bullets. Two bullets – a 175-grain 7mm and a 212-grain .30 – are for handloading only, as they’re very long.

Bullet length has much to do with downrange performance. Long bullets are heavier, start slower than shorter missiles of the same nose profile. But with lower BCs, short bullets decelerate faster and drop more sharply at distance. They also carry less energy to game far away.

Now, if you boot long, wind-slippery bullets fast, you get flat flight and sledgehammer hits from the muzzle to, um, as far as you can aim. The cost: recoil.

“A rocket. But to what purpose?” In 1997, as Weatherby introduced its .30-378 Magnum, few gun scribes thought it practical.

Well, scribes aren’t always right. Nineteen years later, the AccuMark .30-378 consistently ranks among Weatherby’s top sellers!

How could that be? Performance. The most practical product seldom snares headlines or prompts a market frenzy. Fuel misers don’t grace the covers of hotrod magazines. War-planes, from Mustangs to MIG-21s, aren’t celebrated for economical thrust.

Years ago, beleaguered by canyon winds in a smallbore match near La Grande, Oregon, I finished to find a crowd gathered well behind the line. “Hey, you gotta try this!” A fellow beckoned me over.

The rifle he handed me wore a long, heavy barrel and a beefy stock. “It’s a wildcat, a .338 on the .378 Weatherby.” With its target scope, it weighed as much as an armload of firewood. “Watch that rock across the river.” I squinted into the sun. The slab of basalt seemed a township away. Loading a cartridge a little smaller than a bottle of Pepto Bismal, he bellied into the grass. I plugged my ears. The barrel lifted at the rifle’s roar. The rock disintegrated in an explosion of dust. Whack!

I accepted the rifle and muffs, lay down, steadied the .33/378 on its bipod and demolished another stone. Thankful I’d not have to fire 160 record shots with it, I conceded this tornado was great fun!

The .338 K-T (Keith-Thompson) is probably best-known of .33/378s. Given the few rifle actions big enough to swallow a .378 case, and its limited utility, necking Roy’s biggest brainchild to .30 seemed a pointless exercise. I’m told Weatherby pursued the project largely because Redstone Arsenal had asked for a cartridge that would achieve 5,000 ft/sec!

The .30-378 kicks 165-grain Nosler Ballistic Tips at 3,500 ft/sec – a lap ahead of any hunting load for the 7mm Remington and .300 Winchester Magnums. But such power begs heavier, stronger bullets:

| 180-grain Barnes TSX | Muzzle | 100 yds. | 200 yds. | 300 yds. | 400 yds. | 500 yds. |

| Velocity, ft/sec | 3360 | 3132 | 2916 | 2709 | 2513 | 2324 |

| Energy, ft-lbs | 4513 | 3921 | 3398 | 2935 | 2524 | 2160 |

| Arc, inches | -1.5 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 0 | -8.1 | -21.8 |

| 200-grain Nosler Part. | Muzzle | 100 yds. | 200 yds. | 300 yds. | 400 yds. | 500 yds. |

| Velocity, ft/sec | 3160 | 2955 | 2759 | 2572 | 2392 | 2220 |

| Energy, ft-lbs | 4434 | 3877 | 3381 | 2938 | 2541 | 2188 |

| Arc, inches | -1.5 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 0 | -9.1 | -24.3 |

AccuMark rifles in .30-378 have become popular with people who take cross-canyon shots at elk. Penetrating after violent impact up close, bullets like Nosler’s Partition and AccuBond, Swift’s A-Frame and Scirocco and the Barnes’s TSX bring more than a ton of energy to 500 yards. As my last three elk fell at an average range of 27 steps, the .30-378 belongs in other hands. But it is the king of .30s at distance. Hunters a quarter-mile away can count on its bullets plowing flank-to-off-shoulder in elk while unpacking 2,350 ft-lbs of energy. Such thrust could turn a once-in-a-lifetime chance into antlers for the records book.

Military service has given the .338 Lapua press coverage denied cartridges designed for hunting. (At this writing, the longest rifle shot made against an enemy was fired in Afghanistan by an Australian sniper in 2012. A GPS unit gauged the range at 2,815 meters, or 3,079 yards. The shooter is “unknown,” as he and a fellow sniper shot at the Taliban commander simultaneously. One bullet struck.) The Lapua, with the .340 Weatherby Magnum, 8.59 Lazzeroni Galaxy and .330 Dakota, draws on a growing stable of sleek .33 bullets that also deliver fine terminal performance in game. But though recoil is less brutal than that of the more recent .338/378, it’s formidable. Unbraked, hunting-weight rifles can loosen your molars.

Solution: lighter bullets. To get the long, sleek profile that delivers a high BC, you’ll want a sub-33-caliber magnum. The .264 Winchester, 7mm Remington or .300 Winchester Magnums, for example. Or, a step up in case size, the newest 6.5mm fire-breathers.

Still fresh to many shooters, the .26 Nosler came along early in 2014. It’s fashioned from the .404 Jeffery, a 1910-era cartridge whose rim fits bolts sized for the .532 rims of belted rounds. Belt-free design yields greater forward case diameter and, thus, capacity. The .26 drives 129-grain AccuBond Long Range bullets at 3,400 ft/sec, 140-grain Partitions at 3,300. A Nosler 48 rifle gives me .8-minute accuracy.

The 6.5-300 Weatherby Magnum appeared as a wildcat more than 50 years ago. Paul Wright of Silver City, New Mexico used it in 1,000-yard competition. P.O. Ackley wrote of the 6.5/300 Weatherby-Wright Magnum clocking 3,400 ft/sec; Alex Hoyer of Mifflintown, Pennsylvania famously built rifles for it.

A .264-bore lightning bolt, the 6.5-300 Weatherby looses 127-grain Barnes LRX bullets at 3,537 ft/sec. Passing 500 yards they match the muzzle speed of 156-grain bullets in the 6.5×55! A 6.5-300 Mark V zeroed at 200 yards puts bullets within 2 1/2 vertical inches of center to just over 300. The 127 LRX carries more than 1,000 ft-lbs nearly 900 yards! Weatherby loads Swift’s 130-grain Sciroccos and 140 A-Frames (3,476 and 3,395 ft/sec) too. Unlike most Weatherby ammo, 6.5-300 rounds are produced in Paso Robles.

“Barrel-burners,” scoff critics. I recall the .264 Winchester Magnum so indicted at its 1958 debut. While high pressure and velocity do accelerate throat erosion, the most ambitious 6.5mm, 7mm and 30-caliber loads were fashioned for hunting rifles. Big game hunts include little shooting. They don’t require strings of fire that put many bullet through hot bores. Roy Weatherby adored his .257 Magnum, then as now thought hard on barrel throats. Though I’ve used this and other “over bore capacity” magnums, and chatted with hunters who carried them for decades, I’ve not seen a barrel “shot out” by such a cartridge.

And I suspect most hunters with rifles a bit rough in the throat would cheerfully reply: “But she’s taken lots of game, and she still shoots well out yonder.”

Wayne van Zwoll has published 16 books and roughly 3,000 magazine articles on firearms and hunting. Five of his most popular books are: Shooter’s Bible Guide to Rifle Ballistics ($20), Shooter’s Bible Guide to Handloading ($20), Mastering Mule Deer ($25), Mastering the Art of Long-Range Shooting ($30) and Gun Digest Shooter’s Guide to Rifles ($20). Limited numbers are available, autographed, from Wayne at 2610 Highland Drive, Bridgeport WA 98813. Please add $4 shipping.

Stay Connected

- Got a Break in the Montana Missouri Breaks

- It Took Six Days but We Finally Slipped One Past the Bears and Wolves

- No Mule Deer This Fall – Whitetail TOAD!

- An Accounting of Four Idaho Bulls (Elk)

- Arizona Deer Hunt 2019: Good Times with Great Guys

- Caught a Hornady 143 ELDX Last Night

- Cookie’s 2019 Mule Deer Photo Run

- Let’s See Some Really Big Deer

- Alaskan Moose Hunt Success!

- Take a Mauser Hunting: An Important Message From The Mauser Rescue Society!

- Welcome 16 Gauge Reloaders! Check In Here.

- Off-Hand Rifle Shooting – EXPERT Advice

- BOWHUNTING: A Wide One!