Don’t Sell Reloading Dies!

by John Barsness

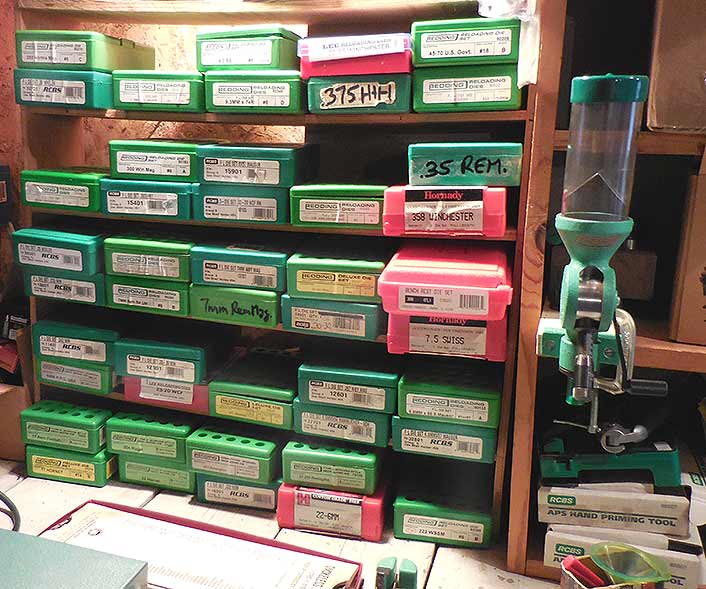

A wide variety of dies can help solve reloading problems.

ANYMORE, one of my basic rules of reloading is not selling any loading dies. The only exception is when I absolutely have to, such when selling a rifle in an obscure or wildcat chambering. Otherwise I keep ‘em, because a wide variety of dies can help solve reloading problems.

As an example, a number of years ago I bought a rifle in 7mm Remington Magnum. This wasn’t my first rodeo with the round, and I had a bunch of brass fired in another 7mm RM. After full-length sizing one, and then long-seating the bullet I wanted to work up a load for in the empty case, the round wouldn’t fit in the chamber. This was expected, because of the long-seated bullet, so I seated the bullet a little deeper and tried again. The round still refused to chamber.

I seated the bullet much deeper, and the same thing happened. I sized another case, and it wouldn’t chamber even without a bullet seated. Duh! Obviously the chamber of my previous rifle had been larger, and full-length sizing didn’t reduce it enough for the new rifle’s chamber.

Now, the obvious solution was new brass, but for the past 30-some years I’ve lived in small Montana towns where new brass isn’t found in every store, or even any store. I might have found 7mm Remington ammunition at one of the local “inconvenience” stores, but I’m not crazy about buying new ammo when there’s already paid-for brass right there on the bench.

However, on a nearby shelf there were dies for several other belted magnum rounds, some for calibers larger than 7mm. I tried them, and found my RCBS .300 Winchester Magnum full-length die was slightly tighter than the 7mm Remington die, and allowed the fired brass to fit my new rifle’s chamber.

I’ve since run into the same basic problem not only with brass fired in another rifle, but occasionally with new brass in rifles with tight custom chambers, and so far have always been able to solve the problem with one of my other dies. Now, you can buy special dies for sizing down the heads of oversized cases, but they’re kinda pricey, especially compared to a .300 Winchester Magnum die purchased for $11.49 back in 1988.

Luckily, the same thing can be accomplished with “.30-06” head-size brass (which is actually 8×57 head-size brass, since the .30-06 is a semi-copy of the old German round) by using commonly available .45 ACP carbide dies. I learned this trick from a Steve Timm article years ago, and even though I don’t own a .45 ACP anymore (we might get into why some other time, and might not) the dies are still there on my shelves.

Often dies for one cartridge can also be used to neck-size another. Right now I have a 6mm Lee-Navy sporter made by Winchester. The 6mm Lee-Navy round was the parent case for the .220 Swift, and even though the 6mm case has a longer neck and slightly smaller rim diameter, simply necking up Swift brass and seating bullets with my .243 Winchester dies works fine. Yeah, I could buy a genuine set of Lee-Navy dies, but like all other specialized dies they’re pricey — and often not even available. Plus, the pressures of my handloads are so low there’s never been any need to full-length size the fired brass.

I’ve done the same thing with .358 Winchester dies when loading .35 Remingtons, as well as other cartridges. Now, I did eventually buy some .35 Remington dies, but couldn’t find any in local stores (even in nearby “big cities” of over 20,000 people), so had to mail-order them. In the meantime I could go ahead and shoot my rifle. It’s also handy to be able to test a rifle without buying another set of dies, especially one that’s been loaned by a manufacturer, and I’ve also done it with the rifles of friends who can’t get their rifles to shoot accurately.

Sometimes a combination of dies can be used to form an oddball round. On example is the German combination gun my wife Eileen bought a decade ago at the Wisdom, Montana gun show. (Wisdom is even smaller than the smallest town we’ve lived in, but they do have a gun show. Supposedly it’s held in the community hall, but a lot of it spills into the streets.) The shotgun barrel was 16-gauge, typical in German guns, and the rifle barrel was supposedly chambered for the 9.3x72R, a long, thin, straight case that originated as a black powder round. The owner even kicked in a box of smokeless RWS factory ammo, half of which had been fired in the rifle.

As soon as we got home I ordered some dies and more brass, and started trying to figure out the bullet problem. The 9.3x72R doesn’t use the typical bullets of more modern 9.3mm rounds, which start at 232 grains get bigger. Instead it uses bullets around 200 grains, at around 2000 fps.

One solution that came to mind was paper-patching .35 caliber bullets, so I slugged the bore. Lo and behold, it was .35 caliber! Actually, it was probably supposed to be 9mm, but bores in older German rifles can definitely vary, despite the German reputation for precision, but the grooves measured .358”.

This simplified bullet selection enormously, but complicated the loading-die situation. As expected, the RCBS dies I’d ordered didn’t squeeze the neck down sufficiently to hold .35-caliber bullets — and neither did my .35 Whelen die, since the 9.3x72R brass was too thin. Well, duh again! I tried my carbide .357 dies and they worked perfectly, and not just for neck-sizing, but mouth-flaring and bullet seating. The rifle turned out to shoot very well with 180-grain Speer flatnose bullets and enough IMR4895 for a velocity of a little under 2000 fps. And it knocks the snot out of deer out to 150 yards, as far as Eileen will ever shoot the gun at big game.

My .221 Fireball dies are a combination of parts from two sets of dies, because I found out they size the neck of Remington just perfectly without using the expander ball. This is ideal, since the necks come out of the die perfectly straight, instead of being pulled off-center a little by the ball. So I substituted the expander/decapper rod from a .17 Remington die that wasn’t being used. All it does is punch out the used primers, but that saves the second step of running the case through my Lee decapping die.

Sometimes other dies can help when you need to neck cases up or down considerably, serving as intermediaries between very different neck diameters. I’ve done this many times, again without having to buy special dies.

Along with stacks of dies, I also keep a selection of Lee Loader hand-tools around. They don’t get used for actual loading much anymore — though they make great ammo when they do, since they’re similar to the specialized hand-dies used by benchrest shooters. But they do help remove primers that somehow get stuck in sideways, and sometimes perform other odd tasks.

But perhaps the most basic reason not to sell dies is the one that took me the longest to learn. I used to sell dies whenever I got rid of a rifle in that chambering, figuring I’d had my fun with that cartridge and would never need the dies again. Then, of course, I eventually ended up with another .264 Winchester Magnum or .35 Remington, had to buy dies, and found that of course they’d gone up in price since my original $11.49 investment.

Which is why my loading room has two sets of die-shelves, one full of “active” dies, for rifles I own and load for right now, and one full of “inactive” dies, which in reality are simply resting until I buy another rifle in that chambering, or have to solve some reloading problem, without heading to the “big city” or spending more money. In fact, over the long run, not selling dies has actually saved money. Which is why those .221 Fireball dies are still around.

John’s new book Modern Hunting Optics and other great stuff can be ordered online at www.riflesandrecipes.com.

Stay Connected

- Got a Break in the Montana Missouri Breaks

- It Took Six Days but We Finally Slipped One Past the Bears and Wolves

- No Mule Deer This Fall – Whitetail TOAD!

- An Accounting of Four Idaho Bulls (Elk)

- Arizona Deer Hunt 2019: Good Times with Great Guys

- Caught a Hornady 143 ELDX Last Night

- Cookie’s 2019 Mule Deer Photo Run

- Let’s See Some Really Big Deer

- Alaskan Moose Hunt Success!

- Take a Mauser Hunting: An Important Message From The Mauser Rescue Society!

- Welcome 16 Gauge Reloaders! Check In Here.

- Off-Hand Rifle Shooting – EXPERT Advice

- BOWHUNTING: A Wide One!