Revolvers Make Riflemen

by Ken Howell

An earlier version of this article appeared in Varmint Hunter Magazine, October 2003. Revised by the author, especially for Smokelore.

ALL RIGHT, now you’ve equipped your favorite varmint rifle with a bench-rest barrel and stock, a set trigger, an excellent scope and mount, even a Harris bipod on the fore-end and an Accu-Shot hind foot under the butt. On your loading bench, you have a fine press, a superb set of dies for that great rifle’s wonderfully accurate cartridges, and all the latest and best handloading accessories and components. You’ve just been loading a fresh lot of your rifle’s favorite powder and the most-accurate bullets that you can get, using meticulously prepared matched cases all from the same lot.

You’re shooting hundreds of prairie dogs, from a portable Gibraltar like the BR Pivot bench, with the finest ammo that you’ve ever developed, and you’ve been scoring on the highest percentage of long-range field shots that you’ve made in your life. You’re the best shot that you’ve ever been. You’re a rifleman ?but most likely you’re not (yet) the best shot that you can be, even though you can’t think of another thing that you can do to increase your shooting skill.

How would you like to be an even better shot with that dream rifle and all that perfect ammo? You can. Easily. And you can have even more fun as you become an even better rifleman.

Anyone can fairly easily develop a modicum of skill with a rifle. It’s not that easy to develop comparable skill with a handgun. A handgun identifies and magnifies every bad shooting habit that a rifle lets you get by with. It can help you overcome them?and it’ll show you clearly when you’ve licked them. The bigger, bulkier, heavier rifle absorbs some of your shooting errors?but the smaller, lighter handgun responds to every error so clearly and so obviously that you can’t ignore them. When you develop any reasonable level of shooting skill with a handgun, you will automatically and dramatically increase your skill at shooting a rifle.

Start with a Revolver, Not an Auto

Get yourself a good long-barreled .22 Long Rifle revolver and a brick or two of any good .22 Long Rifle ammo, and shoot, shoot, shoot. Get a revolver, not an auto. I use and enthusiastically recommend a Taurus “Silhouette” model with a twelve-inch barrel. It’s a well crafted, economical revolver that’s especially suitable as an accessory “simulator” for developing superior shooting skill with a rifle that you know is capable of shooting better than you can. This Taurus of mine is more than just a nice piece to start with ?it’s a long-term keeper. I intend to take mine into the crematorium (unloaded!) with me when I go.

Shooting either type of handgun will, of course, bring to your attention any number of your bad shooting habits, but a revolver makes a much better corrective training device. It’ll make you painfully aware of even that slight flinch, for example, that you can’t detect when you’re shooting a rifle. To shoot any handgun well, you will have to develop a much higher degree of mastery over sight picture and trigger control than you can easily develop with the relatively forgiving rifle.

Shooting a revolver will show you why you miss and will help you overcome those shooting errors that you’ve never suspected were affecting your shooting. With the help of another person, a revolver can reveal the slightest flinch or the slightest sideways deflection of the gun with the trigger finger. The drill is to have the other person load the revolver for you, now and then leaving one or more ?or all ?of the chambers in the cylinder empty without telling you whether any chamber is empty. Don’t check the cylinder ?just take the gun and shoot. When you aim and pull the trigger on an empty chamber, you’ll see ?with crushing?embarrassing clarity ?the slightest flinch or sideward push from an untrained trigger finger.

Shoot ?at every possible opportunity. Since a revolver is so much smaller and lighter than a varmint rifle ?and .22 Long Rifle ammo is so much lighter and cheaper ?you’ll have a lot more opportunities to shoot. Even dry-fire practice in your bedroom or living room is easier with the revolver than it is with the rifle.

On the good side, of course, you’ll see with great delight and satisfaction whenever you don’t flinch or deflect the aim. The revolver, when you use it carefully as a shooting simulator or training device, diagnoses your problems, helps you correct your bad habits, and shows you when, how, and how much you’re increasing your skill.

Start with a Good .22 Revolver

Don’t even consider taking up a center-fire handgun of any kind or caliber until you’ve developed some handgunnery skill with a .22 Long Rifle revolver. Even if the much greater expense of shooting center-fire ammo doesn’t bother you, the greater noise and recoil of the center-fire handguns make them much less suitable for revealing your bad shooting habits and developing those crucial shooting skills.

Shun junk. You don’t need the absolute best .22 revolver there is ?you may not even know what that is (I certainly don’t) ?but you do need a revolver that’s a good bit better than a lot of the junk that’s out there. Don’t go for now with a cheap revolver that will soon make you wish that it were a better one, one that you may find yourself stuck with because nobody else will want it when you get ready to get a better one.

Especially if you’re a beginning handgunner?you don’t want to start with anything that’s more powerful or more expensive than a good .22 Long Rifle revolver. If you take-up revolver shooting as a training regimen to make you a better rifleman, start with a .22 Long Rifle revolver. If you take up revolver-shooting as the great sport that it is, in its own right, start with a .22 Long Rifle revolver. Whatever you plan to achieve in riflery skill, start with a .22 Long Rifle revolver. Whatever you plan to achieve in handgunnery skill, start with a .22 Long Rifle revolver.

Get one with at least a four-inch barrel ?better yet, get one with a barrel six inches long or even longer. When a friend first told me about the Taurus “Silhouette” revolvers with twelve-inch barrels, I sneered at the idea of that long a barrel on a revolver. Then he let me borrow a Taurus .22 Magnum with the twelve-inch barrel, and handling it won me over. I sent the .22 Magnum back to him and bought its twin in .22 Long Rifle. Then I bought another ?same model ?in .357 Magnum. Later, I added yet another like it, in .44 Magnum.

I’ve had a love affair with revolvers since the early 1950s, even during a thirty-year parallel love affair with auto pistols, but I never knew or suspected how much fun and satisfaction there is in shooting these revolvers with super-long barrels.

Veteran handgunners have long noticed that handguns with shorter barrels (four inches, say) are easier to learn to shoot well, while those with longer barrels are a bit harder to shoot well at first. Yet once you’ve learned how to handle a handgun well, you’ll be able to shoot better with the longer barrel. Especially if you’re taking up handgunning as a means of diagnosing and curing your shooting errors and in doing so, increasing your skill as a rifleman, the same quirk that makes the long-barrel handgun harder to shoot well at first (and easier to shoot well when you’re more skillful) make it the better choice for your first handgun.

The longer sight radius of the longer barrel makes your sighting wobbles more obvious to you, so the beginner tends to tighten-up more and to try harder to make the thing settle down ?which just makes the shakiness worse. The shorter sight radius of the short-barrel handgun covers a multitude of sighting errors, making it easier to hold, to aim, and to shoot with a modicum of relaxation and ease. But masking your errors is not so good in the development of shooting skill.

The longer barrel does force you to concentrate more on your hold, your sight picture, and your trigger pull ?which is exactly the reason the long-barrel revolver is the better handgun to start with if your purpose is to use it as a training device to help you become a better rifleman. You want to learn to combine concentration with control, not to get by with the same shooting errors or bad shooting habits that a rifle so effectively forgives and hides from you. You want to see where you need to improve your control, and you want to learn how to improve your control of the gun without tightening-up too much.

Then, once you’ve mastered shooting the revolver with the longer barrel, you’ll be able to shoot it much more accurately than you can shoot one with the shorter barrel ?and for the same reason: that you can then see and correct even slight errors in your hold, your aiming, and your trigger pull.

“Cheat” When You Shoot

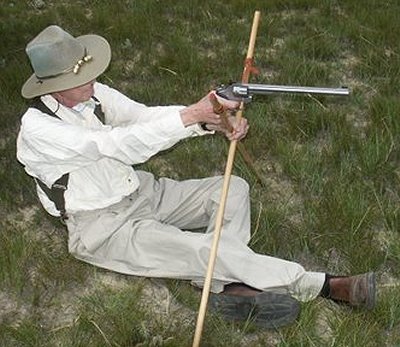

Invariably, whenever someone picks up my Taurus “Raging Hornet” ?a very heavy revolver in .22 Hornet, with a 10 inch barrel and full-length barrel underlug he rams it forward using only one hand, grins ruefully, and makes some comment about its being “too heavy.” In years long gone, I shot .22s, .38s, and .45s in matches and in the necessary preliminary practice sessions before those matches, and in all those sessions?I held my handguns out very unsteadily in one hand, just as I hold ’em while shooting for score in a match. I still shoot handguns this way sometimes, but in field shooting, anything that supports and steadies the gun is a legitimate hold.

Once for all time hence, get rid of the notion that the only right way to shoot a handgun is to hold it out as far ahead as you can stick it, in one hand at the far end of a horizontal arm. Hold it with both hands, prop it, brace it, rest it on anything that’s handy and reasonably solid. There’s no sense and not much to gain in handicapping yourself with a shaky, wobbly shooting arm when you don’t have to.

A relatively minor point, but not a silly or minor notion to be set aside, is the tendency of the revolver to be safer to handle than the automatic pistol. Or, to say the same thing more candidly and accurately, most beginning handgun shooters tend to handle revolvers more safely than they handle automatic pistols.

Squeeze Blood out of a Stone

First, though, you want to train your shooting hand and trigger finger. You want a revolver that’s capable of single-action shooting but not necessarily a single-action-only model like the Ruger Single-Six with its typically long hammer fall. (“Single-action” means that you have to cock it manually just before each shot, then aim and shoot it. This term comes from the fact that in this kind of shooting, pulling the trigger does just one thing ?it fires the gun ?nothing else.)

Hold your shooting hand in front of you at about eye level, with your upper arm almost horizontal and your forearm more or less vertical. Imagine yourself holding a hard, unripe potato with your thumb and the three lower fingers of your shooting hand (leaving your trigger finger free). With your thumb not touching any finger, squeeze that imaginary potato with your thumb and three grasping fingers ?squeeze hard? as if you’re trying to squeeze Hoppe’s 9 out of that imaginary potato. (No, don’t make a fist. Keep your thumb and your three lower grasping fingers curled, with a tunnel of space inside as if they’re really holding an invisible potato.)

Now curl your relaxed trigger finger and move it back as if you’re pulling a trigger with it. If ?as most shooters do on their first try ?you see your thumb or grasping fingers move with the pull of the trigger finger, you see one problem with your trigger pull. Your trigger finger must move completely independently while your thumb and grasping fingers don’t move at all. Concentrate on selectively controlling your grip, and pull until you can squeeze some Hoppe’s out of the spud with your very tense thumb and grasping fingers, and at the same time, with a relaxed trigger finger, pull an imaginary trigger without the slightest movement of the fingers squeezing that spud. When you’ve developed this selective, independent control of your trigger hand, you’re ready to train that trigger finger to pull straight back?without the slightest sideward movement.

Hold a bolt, a pencil stub, a short dowel, a rifle cartridge, or anything else handy that spans the distance from the pad inside the first joint of your curled trigger finger back to the soft web between the base of your thumb and the palm of your hand. Hold it there just tight enough that you don’t drop it. Pull back on it a fraction of an inch? as if you’re pulling a trigger. When you can ?every time ?pull it straight back without the slightest sideward tilt, you’ve trained a bad habit ?that you probably didn’t suspect that you had ?out of your trigger finger.

Use the Issue Sights

Resist the urge to put a scope or other fancy optical device on that revolver, at least while you’re using it as a training aid. I prefer and recommend an adjustable rear sight ?indeed, I have only one handgun with a fixed rear sight ?that one is a self-defense carry ?an automatic that I haven’t fired, that I hope I never have any need to fire, that I don’t expect to ever need for shooting at any great distance. All the rest of my handguns, all devoted to fun shooting?have adjustable rear sights ?which I must confess that I very seldom have to adjust.

Practice, Practice, Practice (Have Fun!)

Have fun while you learn. You may not do so well at first, but don’t let the poor shooting in your first few tries discourage you. Grit your teeth, dig-in your heels, grab the bull by the horns?and don’t let go until you’re on top. Shoot more, not less. Shoot, shoot, shoot at every opportunity, which you’ll find more frequent if you keep that revolver handy.

A friend of mine, a well known shotgunner, died of old age and orneriness without ever trying Crazy Quail at Nilo Farms. He had several opportunities to try it but always turned away because he knew that he couldn’t hit ten straight. What a lot of great fun he missed! Crazy Quail is tough, all right. I shot it four times, and I’m not ashamed to tell you that I hit only four, two, none, and four out of ten in those four stints. I had a ball! Because it’s so tough, every bird that my shot pellets reduced to clouds of black shards was a “gotcha” victory?and those that I missed were “comes with the territory,” not something that I felt any urge to cuss or to get red-faced about. Crazy Quail is the only clay-bird game that makes any sense to me. It’s practical?not cut-and-dried predictable, much more like shotgun hunting than any other clay-bird game that I know.

So it is also with learning to handle a revolver well. Shooting a small-caliber revolver may not be practical, useful, or even greatly entertaining for you in its own right, but it’s very useful and practical for any shooter who wants to be a better rifleman. Revolvers make riflemen.

You may not be able to hit a dinner plate from half-way across your back yard at first, but start with small target objects. One thing that you’re looking to learn is how to aim fine and how to hold, hold, hold that fine aim while you touch-off a round. Aiming at the middle of a dinner plate won’t develop as much shooting skill as aiming at thumb tacks or empty brass. When you’re dry-firing at home, “shoot” flies on the wall, even tinier specks just large enough for you to see ’em. You’ll learn how to sight with the middle of the top of your front sight, which develops a lot more skill, a lot sooner, than sighting with the whole blade at the vague middle of something bigger that shows all around the front sight.

Once you’ve learned to shoot the .22 well, then you’ll do well with a good center-fire revolver. But if you get the huskier gun first, you’ll seriously retard the development of your skill with a handgun. It’ll encourage flinching and will make your flinch much harder to overcome. Repeated shooting with a larger-caliber handgun ?especially at first, when you’re just getting accustomed to shooting a handgun ?will make your shooting arm shakier and shakier as you continue to shoot it.

Concentrate on the front sight and let both the rear sight and your target go fuzzy. You can still line-up the front sight with both the rear-sight notch and the desired aiming point on the target, as long as the front sight looks sharp. A front sight that you keep in sharp focus is one of the best “secrets” of shooting a handgun with skill?much more important than having a rear sight or a target in sharp focus.

The front sight shows you where the muzzle is, and where it’s pointing when the bullet comes out is where that bullet’s going to go. A fuzzy front sight is just too easy to let wander off a bit without your noticing. Sight control is front-sight control. You’ll find that keeping it in sharp focus requires heavy, stubborn concentration at first ?another aspect of learning or improving the basic skill of good sight control.

Paragraph

Develop skill with a typical issue square-notch rear sight and flat-top Patridge front sight on a revolver, and you’ll increase your skill with a powerful scope on a rifle. Or with any other kind of sighting apparatus on any kind of gun that you have to aim fine, for that matter.

And it’s great fun.

###

________________________

Copyright 2007 Dr Kenneth E Howell. All Rights Reserved.

Stay Connected

- Got a Break in the Montana Missouri Breaks

- It Took Six Days but We Finally Slipped One Past the Bears and Wolves

- No Mule Deer This Fall – Whitetail TOAD!

- An Accounting of Four Idaho Bulls (Elk)

- Arizona Deer Hunt 2019: Good Times with Great Guys

- Caught a Hornady 143 ELDX Last Night

- Cookie’s 2019 Mule Deer Photo Run

- Let’s See Some Really Big Deer

- Alaskan Moose Hunt Success!

- Take a Mauser Hunting: An Important Message From The Mauser Rescue Society!

- Welcome 16 Gauge Reloaders! Check In Here.

- Off-Hand Rifle Shooting – EXPERT Advice

- BOWHUNTING: A Wide One!